GCED Basic Search Form

Quick Search

Vous êtes ici

Nouvelles

By Silvia Montoya, Director, UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), and Gustavo Arcia, Economist and UIS Consultant

Statistical institutes in low- and middle-income countries face significant pressures to collect education data under quarantine. This pressure reflects the need to mitigate the many impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, which threaten the economic and social fabric, as documented by the Committee for the Coordination of Statistical Activities (CCSA), where all heads of statistical units of the United Nations System convene.

Given the difficulties imposed by the Covid-19 crisis, the basic questions for ministries of education, their agencies and statistical institutions are: (i) what data to collect, and (ii) how to collect it, to monitor learning equity.

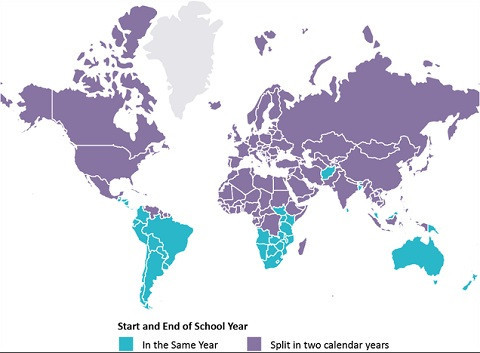

In many countries where the school year is split between two calendar years, there is still about a month of class time left, while in countries where the school year falls within one calendar year, classes are just starting. In the former case, policy decisions on education delivery revolve around temporary measures to bridge the gap between the middle of the second semester and the end of the school year, while in the latter case, decisions revolve around new policies for the incoming school year, such as implementing a reduced curriculum; implementing online and distance education; implementing in-service teacher training on a massive scale; and monitoring student participation and performance on a continuous basis.

School year split around the world

In both cases, education data need to reflect the consequences of school closures and, where available, distance education – at a time when obtaining accurate headcounts of students and teachers is difficult. There have been negative impacts on equity and inclusion during the pandemic, especially in terms of how learning opportunities are shared, with some children likely to suffer more than others. In these circumstances, statistical institutes need to decide which are the most essential education variables that can be collected for immediate use and to monitor the structural changes affecting learning equity that may remain after the Covid-19 crisis is over.

Tracking losses in learning equity and inclusion

A short list of essential indicators is needed that should be collected during the pandemic and in the future. A country-level strategy to manage education data in the pursuit of learning equity during and after the Covid-19 pandemic should include – at a minimum – the collection and reporting of data on:

- Student participation in all platforms of education delivery disaggregated by individual student characteristics, such as gender and poverty

- Teacher participation in all platform of education delivery disaggregated by individual teacher characteristics, such as gender and contract status

- Use of quick and short tests for the frequent measurement of student learning.

Learning under different scenarios of distance and online education will probably also vary depending on a child’s age. Besides differences in learning between well-off students and students in vulnerable conditions, learning losses could be disproportionately larger in the first two or three grades of primary, as children in later grades are likely to be capable of learning more on their own, requiring less direct contact with a teacher. Due to the differences in mental maturity between younger and older children, maintaining a low pupil-teacher ratio in lower grades could be crucial to recovering learning losses. Hence, learning should also be analysed across children’s ages, and measuring and mapping learning equity should be made a policy priority.

The analysis of learning should be linked to the methods of education delivery used in different grades. Access to online education may be less effective among young children than watching canned classes on TV. Analysing the impact of different methods of distance education on the same age group will be useful in establishing clear guidelines for delivery.

How should ministries of education, their agencies and statistical institutes collect these data in the midst of the pandemic? First, they may have to focus on only a few key indicators and collect data from samples of the school and student populations instead of the entire education system. Second, oversampling of vulnerable students (i.e. students in poverty, with special needs, and those who use minority languages) may have to be used to monitor equity. Third, a frequent measurement of learning may have to be implemented to allow the system to compare learning under different methods of instruction and anticipate needs for teacher training, instruction platforms and operational performance. The UIS in collaboration with the World Bank and the Global Partnership for Education is in the process of developing short standardized tests to measure learning under a global proficiency framework. These tests will soon be freely available and accessible through the global commons.

Finally, further background information may be needed to gain a macro picture on school calendar changes, affected examination schedules, adjusted promotion procedures, and remedial education plans.

URL: