GCED Basic Search Form

Quick Search

当前位置

新闻

“After six months of deep disruption, education stands on fragile ground everywhere. Without remedial measures, this crisis will magnify the educational failures that already existed before it”, said UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Education, Ms Stefania Giannini at the opening of the UNESCO global webinar held on International Literacy Day (ILD).

The event brought together more than 500 participants, stakeholders and decision makers from around the world on 8 September 2020. The discussion focused on the theme of ILD 2020, ‘Literacy teaching and learning in the COVID-19 crisis and beyond: The role of educators and changing pedagogies’.

The COVID-19 crisis revealed the unpreparedness of education systems, infrastructure, educators and learners for distance learning, and the fragility of adult literacy programmes. It hit hardest those who were already marginalized, including 773 million non-literate adults and young people – two-thirds of whom are women and 617 million children and adolescents who were failing to acquire basic reading and numeracy skills even before the crisis.

“Adult literacy and education have been absent in many initial education responses of countries and of the international community. Even before the crisis, nearly 60% of governments spent less than 4% of education budgets on adult literacy and education,” said Ms Giannini.

“In this time of crisis that has pushed societies to the limits, let’s make literacy a force for inclusion and resilience, to reimagine how we live, work, and learn for a more sustainable and just development path,” Ms Giannini said and officially opened the global meeting.

Adult literacy educators are central for meaningful literacy teaching and learning

Ms Olfat Abdulatif Al-Sorori from Yemen, one of the literacy educators who have been at the forefront coping with disrupted teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, gave a testimony:

“I have been working as a volunteer in the field of literacy for years and it (COVID-19) has had a great impact on educators in literacy centers in many aspects, including financial and psychological. The material aspects and the economic life has stopped, thus the physical conditions of educators have gotten worse.” said Ms Al-Sorori.

According to a survey conducted by UNESCO Beirut, nearly 70 % of participating programmes in the survey had to reduce or cut the salary of educators, the majority of whom are 20-45 years old and may seek for other sources of livelihoods.

One of the key messages was that it is essential to promote the professionalization of literacy teachers, and guarantee the rights, status and decent working conditions of literacy teachers, while providing continuous professional development opportunities, support and guidance.

A global landscape on literacy teaching and learning in the COVID-19 crisis and beyond

During the first session moderated by Ms Mari Yasunaga, Programme Specialist, Section of Youth, Literacy and Skills Development at UNESCO, the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on youth and adult literacy was reflected from global, regional and country perspectives.

Mr Borhene Chakroun, Director of the Division for Policies and Lifelong Learning Systems at UNESCO Education Sector provided a global picture, emphasizing the lack of policy attention to youth and adult literacy, calling for its integration into national lifelong learning policies, aid policies and the COVID-19 response and recovery plans. A UNESCO impact survey of the COVID-19 crisis on literacy programmes conducted in August revealed that more than 90% of 49 adult literacy programmes were either fully or partially suspended during lockdown.

”The goal today is to focus not only on schools but also on other learning programmes” said Mr Chakroun and presented some key findings from the background paper on youth and adult literacy in the times of COVID-19. He also highlighted the need to further monitor the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on youth and adult literacy for strategic responses, saying that “While there is data on school closures, we know much less about literacy programmes.”

In anticipation of shrinking financing of education due to the crisis, which will affect millions of learners and the future state of literacy, Mr Chakroun stressed:

“Society will not recover if there is no investment at all levels of education, including literacy in a lifelong learning perspective. Equity must remain an important aspect of access to education. We need to cater for the most disadvantaged.”

Ms Rita Bissoonauth, Head of Mission, International Centre for Girls and women’s education in Africa, African Union (AU), said that the COVID-19 lockdown has left learners without access to learning. During the meeting of Ministers of Education, Science and Technology of the AU held in May 2020, all Ministers underlined the use of educational technologies such as television and radio to provide remote learning opportunities for girls, boys, young men and women during the lockdown. But these tools and platforms have not been accessible to many learners.

She called for governments’ action to enhance distance learning, and shared an example of low-cost, solar-powered tablets loaded up with “a toolbox of digital books and learning resources to ‘off the grid’ classrooms with no internet and electricity.”

She also emphasized the vulnerability of girls during the crisis:

“Schools are safe spaces for girls. The girls were unprotected during the pandemic and thus exposed to abuse, child marriage and violence. Governments need to tailor equitable solutions to the impact of the pandemic for learners. Students have undergone anxiety and mental pressure during this pandemic.”

She said that they had launched a campaign to ensure that girls go back to school and called on governments to provide affordable, reliable and accessible internet to all communities and financial support to the most affected families to ensure support and encourage girls and children to return to school when possible.

Mr Mohammad Yasin Samim, Senior Technical and Policy Advisor for Literacy at the Ministry of Education, Afghanistan presented how Afghanistan is sustaining youth and adult literacy provision during the COVID-19 crisis, stressing the importance of political support.

Before the crisis, the Afghan government started the implementation of a plan called ‘National mobilization for literacy’ under the leadership of the president and enhanced governance for adult literacy and non-formal education by establishing committees at the national, provincial, district village levels.

After the outbreak of the pandemic, the government developed a comprehensive education response plan to ensure the learning continuity. He said that some measures deployed for distance learning had proven to be successful, including open space programmes which covered more than 40,000 adults.

Since the provision of online lessons were difficult due to a lack of the necessary ICT infrastructure and capacities of educators and staff, Education radio and TV were used for distance learning. In order to reach people in rural areas, Mr Samin said that the government prepared specific guidelines for learners and officials at provincial and district levels to maintain adult literacy and family literacy courses. In addition to radio and television, WhatsApp groups were created to follow up on learners

Reimagining literacy teaching and learning and the role of educators

Moderated by Mr David Atchoarena, Director of the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, the second session explored how literacy teaching and learning can be inclusive and meaningful and how educators can be supported, from different perspectives.

Mr Mafakha Touré, Expert in education from Senegal, shed light on the centrality of educators. According to him, it is thanks to educators and literacy facilitators that Senegal has been able to make significant progress in literacy. However, usually, adult literacy educators, whose profile is diverse, are poorly remunerated, in low status, and inadequately trained and supported. Often they have to teach with irrelevant curriculum and limited teaching materials.

For policy attention, he emphasized the need to invest in educators and to take comprehensive approaches to educator management, attaching the same importance to formal and non-formal education. In Senegal, primary teacher training colleagues were replaced by a system for education personnel in 2010 to provide continuous versatile training for educators in both formal and non-formal education. This integrated approach was reinforced by a law adopted in 2014.

“They (the facilitators) constitute the backbone of strengthening the education of those excluded from the school system but are also supporting their contribution to the development of their communities through their function as development facilitators, but they still face structural difficulties,” said Mr Touré.

Digital technologies in adult literacy teaching

Ms Judy Kalman, an expert in education and literacy from Mexico, made a presentation about how to harness the potential of digital technologies for literacy teaching and learning with educators. If connectivity is not an issue, technology can open up a lot of possibilities, she said.

The crisis has shown that to ensure the continuity of meaningful adult literacy teaching and learning – during the COVID-19 crisis and beyond – there is a need to build robust education systems and ICT infrastructures, as well as digital skills for managing different modes of teaching and learning that are taking leaners’ needs, aspirations, circumstances and contexts into consideration.

Ms Malman stressed: “Rather than putting technology in the center, it is important to put people in the center. In this way, the approach would shift from what the technology does to how we use it.”

She highlighted the roles of educators in teaching literacy and in enabling learners to construct knowledge. Among other things, educators need a deep understanding of literacy, digital skills, and good understanding of how human construct knowledge in social contexts and how reading and learning is related to the process of knowledge construction.

Cognitive neuroscience and adult literacy learning

Mr Michael Thomas, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Birkbeck, University of London and Director of the Centre for Educational Neuroscience from the United Kingdom, talked about educating the adult brain and how cognitive neuroscience of learning can improve literacy teaching and learning. He presented some findings from his recent research on adult literacy programmes in the developing world commissioned by the World Bank.

“These (literacy) programmes are an important escape route from poverty, yet they are often ineffective. Is there a neuroscience reason; is the adult brain somehow less plastic,” he reflected.

“Adults seem to be better learners in the classroom than children, but adults don’t consolidate skills as children, forgetting more between lessons, and they may need more practice to achieve automaticity, that is easy and effortless automatic reading,” said Mr Thomas.

Adult lives are more complicated: Adults have jobs, are raising families and they have many competing demands on their time. One estimate is that it takes around 2000 hours to learn to read. If you attend an adult literacy programme, say two hours, three times a week for 6 months, one has only completed 10% of that. The other 90% is practice that must be completed at home, squeezed into busy lives.

An important factor to this solution is motivation. Literacy needs to be made personally relevant to the individual, it needs to be a means to an end in their lives rather than a goal in itself. What new things can people do once they can read, is the question. Practice also needs to be supported by social networks of learners because peer support for learning is essential, emphasized Mr Thomas.

Inclusive literacy teaching and learning

On inclusive literacy teaching and learning, Ms Anita Dighe, an expert in literacy and education from India said that the civil society groups would have an important role to play in making literacy teaching inclusive for youth and adults in poor communities. Since literacy is part of a larger struggle for social, economic and political change, there was a need to link literacy learning with a broader vision of social transformation.

Literacy learning could be a leverage to empower communities by the process being dialogical, as they could encourage processes of critical self-reflection, thinking, questioning, exploring, interacting, creating, connecting and discovering. She emphasized that such processes are directly linked to the notion of empowerment in which an individual learns to create, share knowledge, and new tools and techniques in order to change and improve the quality of his/her life.

“These processes would need to be used for empowering communities so that learning communities can be established. The link between the local, the national and the global communities would need to be constantly made so that the local reality can be perceived and understood in the light of the changes taking place at the national and the international levels,” said Ms Dighe.

Inclusive learning requires collaboration, sensitivity to cultures and languages, and the relevance to leaners’ realities, circumstances and contexts. She stressed the need for targeted policies to address changes for specific groups and to design programmes to ensure holistic learning, and to respond to women’s specific needs by establishing separate literacy learning groups for them.

Literacy teaching for empowerment and freedom

As an architect of the REFLECT (Regenerated Freirean Literacy through Empowering Community Techniques), Mr David Archer reflected on achievements of REFLECT approaches. Noting literacy as ‘a political process’ connected to contexts, he stressed that the learning should be relevant to leaners’ lives, and literacy development is part of broader processes towards liberation and transformation.

Mr Archer also alerted to financial challenges due to the COVID-19 crisis which will restrain education budgets, in which adult education would be the first sacrificed.

“The goal should not be to ‘return to before’ as there had been decades of underfunding for adult literacy. We need to see education as lifelong learning, and we must work closely with debt campaigners. We need strategic action on debt, debt justice, tax justice, pushback on IMF economic models that are holding down public sector workers. Increasing equity through education should be a major priority.

Fundamental aspects are recognizing the transforming potential of education, so to increase equality in education we need to have equality in the budget planning. If one is serious about equity through education, adult learning must logically be prioritized,” said Mr Archer.

Mr Atchoarena concluded the session saying that there are no short actions, but implementing inclusive and comprehensive lifelong policies which integrate adult literacy and long-term investments within the framework of SDG 4.

Concluding with a call for investing in literacy teaching and learning in a lifelong perspective

The meeting was closed by Mr Chakroun emphasizing three takeaways: that COVID-19 is a magnifier of pre-existing challenges for literacy learning throughout life, which include: the lack of quality of teaching; too few resources invested in adult literacy teaching and learning; and the lack of qualifications for literacy trainers to make them resilient in situations such as the COVID-19.

There is a need to leverage new knowledge and evidence to support and improve literacy teaching and learning throughout life, and the lack of financial resources in economies will further aggravate the existing lack of resources in literacy if countries do not give special attention to the investment in adult literacy programmes.

The second part of the webinar celebrated the five 2020 edition of International Literacy Prize winners from Nepal, United Kingdom, Ghana, Mexico and Yemen.

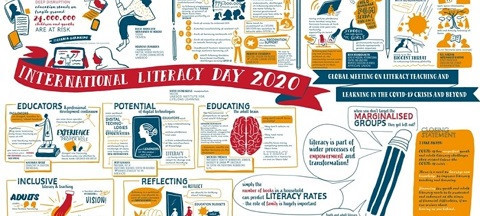

Visual summary from the webinar on UNESCO International Literacy Prize winners

- Learn more about International Literacy Day (ILD) 2020

- Read UNESCO’s press release for International Literacy Day

- Read UNESCO’s background paper for ILD ‘Youth and adult literacy in the time of COVID-19: Impacts and revelations’

- Visit the website for UNESCO International Literacy Prizes

URL: