GCED Basic Search Form

Quick Search

You are here

News

The response of education during the pandemic has revealed the possibilities, both digital and non-digital, to reduce the number of out-of-school children, including those who were already excluded before the COVID‑19 crisis.

By Wongani Grace Taulo, Suguru Mizunoya, Garen Avanesian, Frank Van Cappelle, Jim Ackers

Until about a year ago, being out of school was solely about who you were, where you were born, where you lived and your social and economic conditions. Today, COVID‑19‑related school closures have impacted all children and young people, keeping them out of school for prolonged periods. At its peak, nationwide school closures affected over 90 per cent of the world’s student population resulting in extraordinary challenges to the continuity of learning – particularly for children in marginalized groups. With pandemic school closures, the concept of out-of-school children has taken on a new meaning and attracted increased attention.

In 2018, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics estimated that over 258 million children, adolescents and youth were out of school – one sixth of the global population of this age group. Lessons from previous school closures show that not all children will return to schools when they reopen. However, as schools reopen, there is a desire to reopen ‘wider’, to accommodate those learners who were already out of school pre‑COVID‑19 – but action is needed now to ensure the numbers of out-of-school children do not increase after this pandemic.

Can COVID‑19 lessons help against the global problem of out-of-school children?

Efforts to deliver remote learning have shown us that there is an opportunity to exploit the creativity that has emerged in how education can be delivered through more differentiated approaches beyond schools. We have a window to build on the emerging concept of education being delivered any place, any time, to anyone, especially children from the most marginalized populations.

The energy that has been put into finding innovative ways to keep children learning can be harnessed for solutions to help out-of-school children more generally. The school closures have shown us that we need multipronged approaches to the various needs of children to learn wherever they are, and information and communications technology (ICT) can be one of the keys to these. While there are immediate issues in connecting all children, initiatives like Reimagine Education which includes GIGA, aim to connect all schools in the near future. Beyond schools, universal community access to the internet will be a force for enhancing equity and realizing the right to life-long learning – the pinnacle of Sustainable Development Goal 4. ICT is not a panacea, though, and must be complemented with other modalities of learning.

What can we do as schools reopen? Are there any quick wins?

As schools reopen, we need to extend enrolment to those children who were already out of school pre‑COVID‑19. Similarly, non-formal educational programmes and institutions, including alternative learning programmes (ALPs), should be supported to accommodate the out-of-school children who wish to follow this route.

We also need to incentivize the enrolment of children who were out of school before the pandemic.This can be done by removing financial barriers, providing learning resources, loosening registration requirements and offering flexible programmes, both in school and in non-formal programmes tailored to their needs. In doing this, it is important to engage communities withtargeted back-to-school campaigns and messages to reach out-of-school children, plus strategies to track their numbers.

Enrolling all new entrants into school regardless of age is a key strategy. Monitoring the enrolment of grade/class one entrants will be particularly critical. In some countries, government officials and school staff make door-to-door visits to get all children enrolled.

We also need to change policies which ban pregnant girls from school and allow pregnant girls and young mothers to return to school. The Malala Fund estimates that 20 million adolescent girls may drop out of school due to the impact of the pandemic, including pregnancy, similar to the case during Ebola in West Africa. The Government of Sierra Leone recently overturned a long-standing ban on pregnant girls being in school. Such a strategic decision can make a big difference to attendance.

Addressing all groups of children out of school will increase the chances of success. For instance, some strategies may work for children from poor households, but additional approaches may be needed for children with disabilities. Similarly, it is important to distinguish children who have never entered school from those who entered late or are likely to drop out, and to develop strategies that respond to their unique needs.

What about systemic changes in the medium- to long-term?

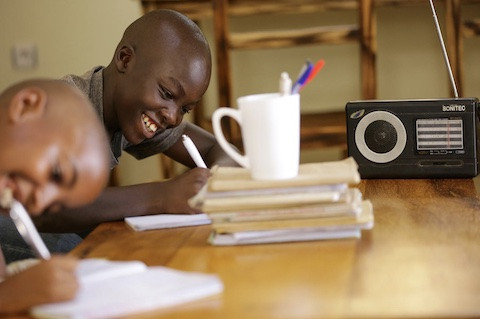

While nothing can replace face-to-face learning, the COVID-19 education crisis has shown the possibility to deliver education beyond the school. Learning can take place anywhere, any time. Adapting remote learning to both online and offline modalities will help reduce the number of out-of-school children. Programmes such as Storyweaver, EkStep, Learning Links and radio education are examples that can be explored to accelerate provision beyond schools.

With many adolescents failing to transition from primary to secondary school, and even fewer to upper secondary education, systemic shifts must ensure remote learning strategies flexible for out-of-school adolescents, allowing them to develop the skills they need for work.

We need to retain those who are in school by institutionalizing early warning systems, to identify the risk of dropout and so prevent the problem. This must include a system for monitoring children’s educational participation, achievement and general well-being at school. The early identification of risks will increase the success rates of interventions and is cost-effective in the long term.

Rethinking school schedules, curricula and assessment, and makinglearning more attractive to all children, not just to academically inclined learners, will also help keep children in school. This can be achieved through flexible school schedules and rethinking ways to assess learners, tailoring approaches to their varying needs and gearing them towards reducing inequalities.

The experiences of remote leaning have also taught us the importance of parental and caregiver engagement in children’s learning. This is a practice that must be institutionalized while ensuring parents and caregivers get adequate support and resources. The Speed School programme in Mali is a good example that can be emulated. Similarly, the contributions of private partners in education must be harnessed beyond the current crisis to explore ways of ensuring that effective innovations remain in place to respond to the long-term needs of OOSC.

Education for all children is a fundamental human right that must be fulfilled at all costs. Quality and inclusive education for all will be key to the COVID‑19 recovery and to securing the current generation’s future. Without creating new opportunities to ensure education, training and work for all, we risk creating disenfranchised societies and further exacerbating socioeconomic inequalities.

We must seize the opportunity now to invest in effective alternative models to school learning, including the development of both digital and non-digital modalities, to help reach out-of-school children and provide them with access to quality education wherever they are, whoever they are.

URL: